1. Introduction

The goal of this document is to identify presentation and layout requirements of Zaima annotation and raise the questions that must be answered where the requirments are uncertain to then fully specify the presentation convention.

This document presents an overview of Ethiopic "Zaima" annotation and evaluates the suitability of available W3C standards for expressing the layout and presentation found in use cases. Characteristic samples have been selected that demonstrate the bredth and depth of the formatting complexity occuring in Zaima annotation. Recommendations are made for the addition or extension to an existing standard only when a mechanism is not available to support a requirement of Zaima presentation. The intention of this approach is to incur a minimal impact upon the existing family of applicable W3C standards and thus minimize the software modifications that would be required to support the annotation convention.

1.1 What is zaima?

Under divine inspiration in the early sixth century St. Yared

(Miazia 5, 505 AD - Genbot 11, 571 AD) devised the system of

over 600 notations (including 10 non-letter symbols)

for his seminal work the

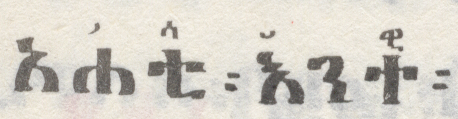

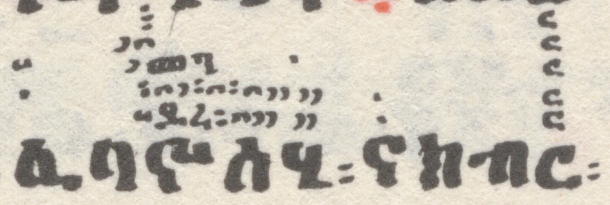

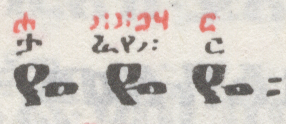

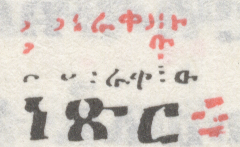

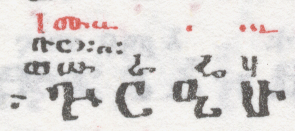

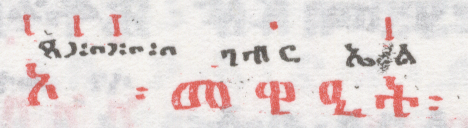

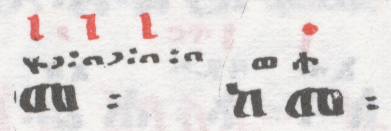

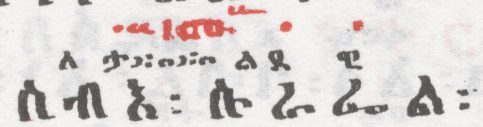

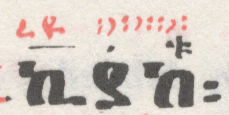

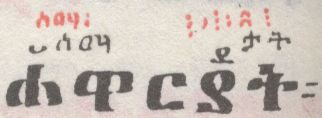

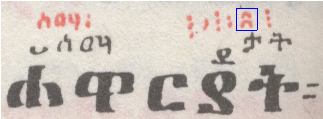

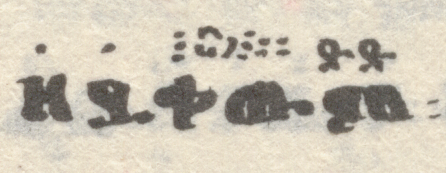

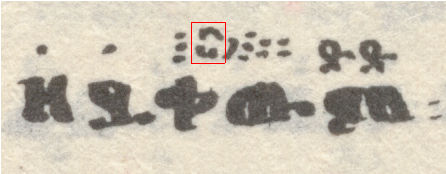

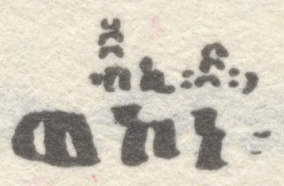

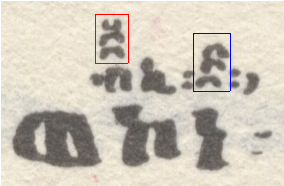

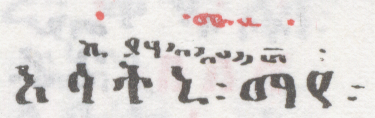

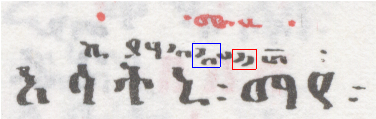

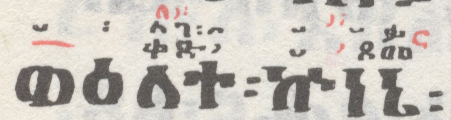

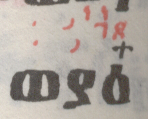

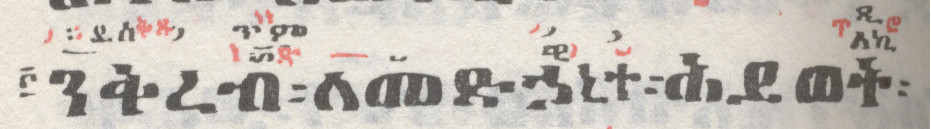

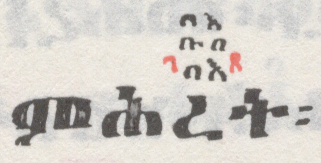

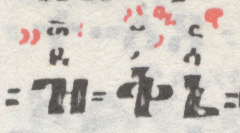

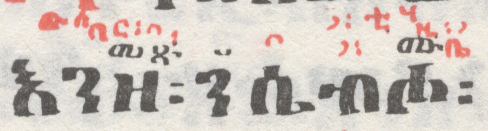

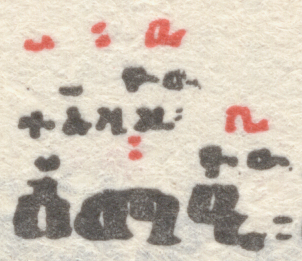

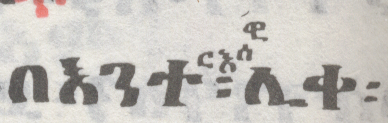

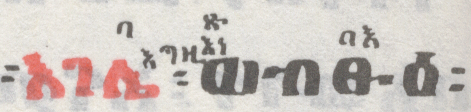

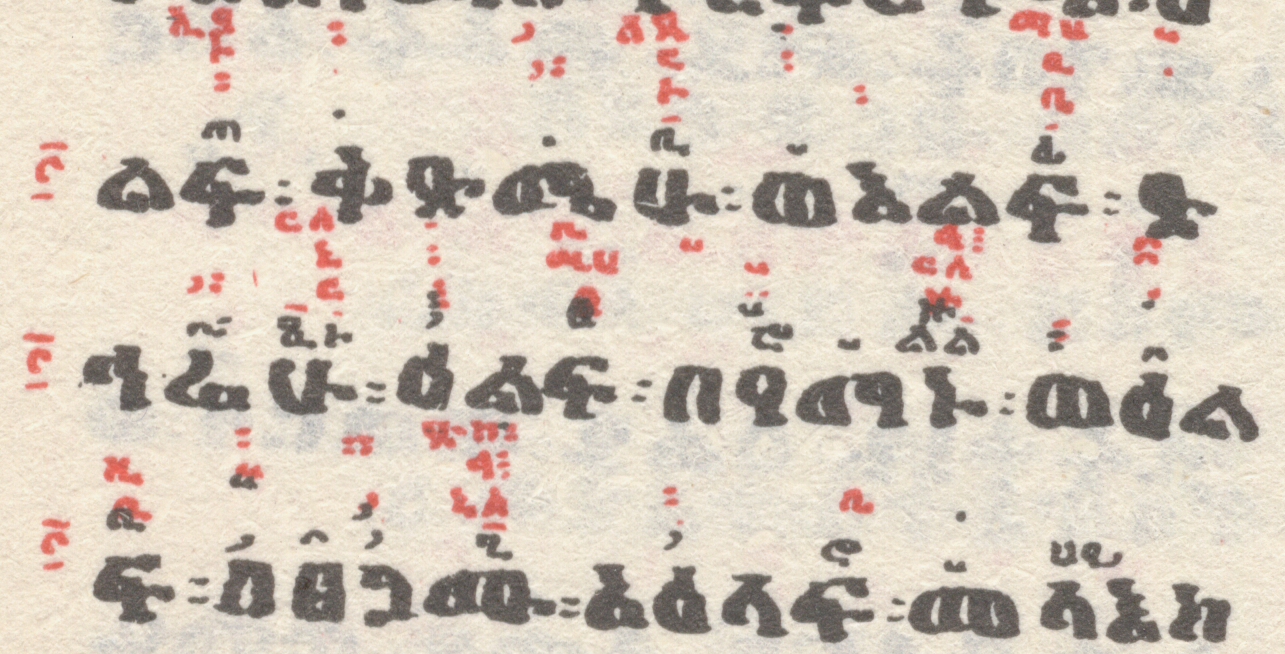

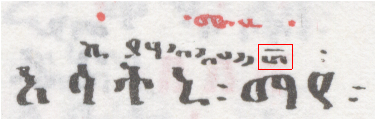

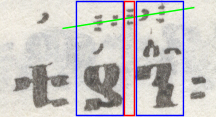

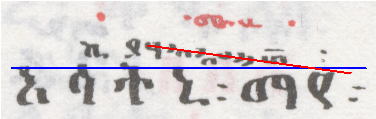

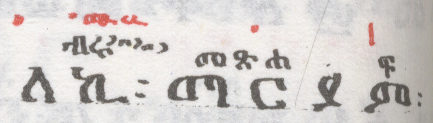

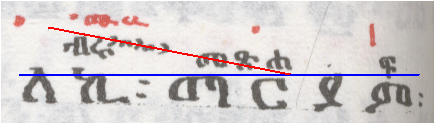

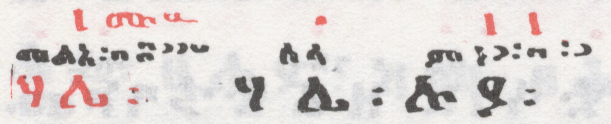

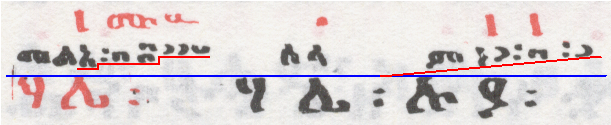

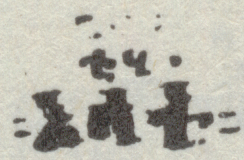

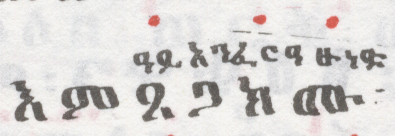

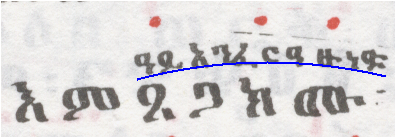

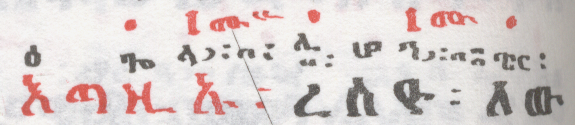

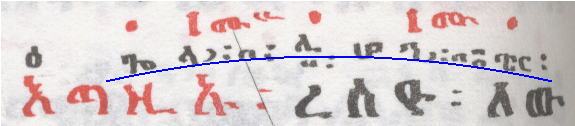

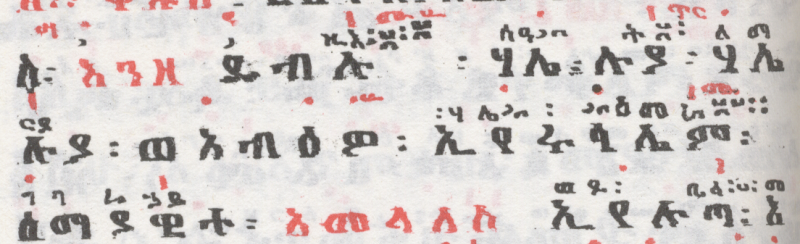

These moods are written in three distinct levels within the inter-linear space above the base text. In order from lowest to highest above the base text the moods are: Ge'ez (ግዕዝ), Izzel (ዕዝል), and Araray (ዓራራይ). The notation text is rendered in size aproximately a quarter to a third the scale of the base text. Izzel notation are written in red to help distinguish the mood from the other two (which in turn do not occur together in the absense of Izzel). When one mood does not exist for a given passage, the text of the upper levels may descend downward to occupy a lower level [Q2]. With the exception of the non-letter symbols (known as "ምልክት"), which may be employed by any of the three moods, the moods have their own distinct lexicons. Thus the mood context of an annotation row is also identifiable by the terms present. The annotation entities in turn will almost always appear in abbreviated form (known as "ሰራየ") to minimize their horizontal footprint in layout as well as to allow for faster rendering by calligraphers. Figure 1.1 shows an example over three lines.

Figure 1.1: A three line example of zaima notation.

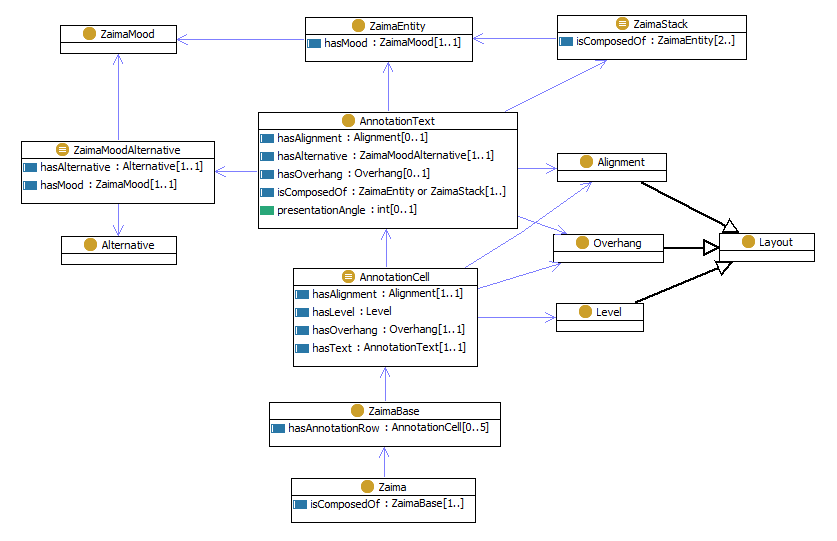

1.2 The zaima box model

The W3C recommendations for Ruby annotation are directly applicable to Zaima practices. The CSS3 Ruby module applies a multi-level box model for describing ruby layout in the the writing practices of Asia. A modified box model is used hereafter to likewise describe Zaima presentation.

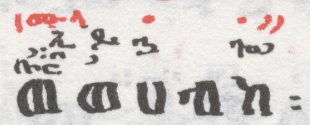

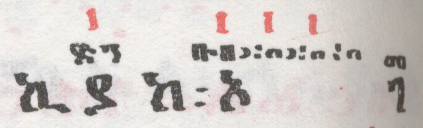

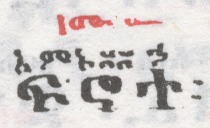

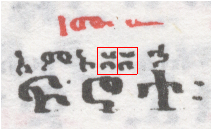

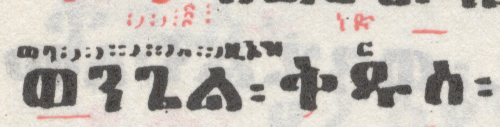

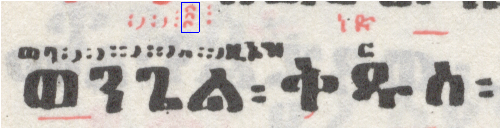

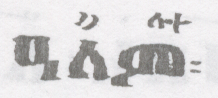

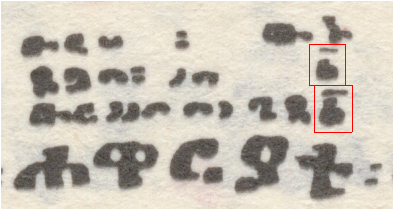

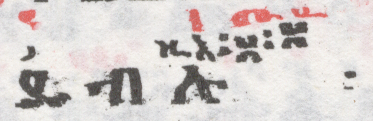

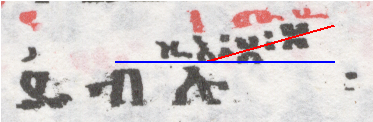

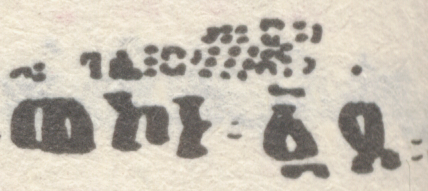

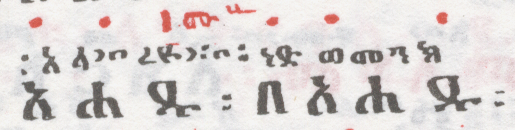

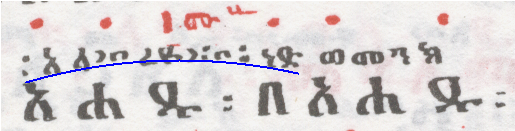

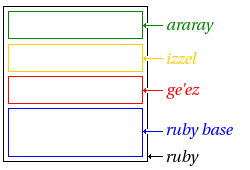

The simplified Zaima box model employs the same ruby base and adds two additional ruby text levels for a total of three. When all three moods exist for a passage their rows occur in sequence as shown in Figure 1.2:

Figure 1.2: Extended Ruby box model.

In practice the occurance of all three moods simultaneously is found only rarely. However, it is common that a single mood will occur twice, and occassionally three times, for a given passage. In these cases, the default, or primary, form of a mood will be at the lowest level [Q3]. The addition occurances of the same mood, considered alternatives, will appear at successively higher levels. The combination of moods and their alternatives maximally produces five levels of annotation text above the base. These scenarios will be illustrated in Section 2. A more comprehensive Zaima model is presented in Appendix A.

1.3 Axioms of zaima annotation

This section contains a collection of assertions for Zaima annotation that should be respected by any application implementing support for Zaima presentation.

[Q4] These rules must be vetted:

- [Q4a] Izzel may not appear by itself.

- [Q4b] Ge'ez may appear by itself.

- [Q4c] Araray may appear by itself.

- [Q4d] Ge'ez may combine with Izzel.

- [Q4e] Araray may combine with Izzel.

- [Q4f] Izzel must appear in red.

- [Q4g] Ge'ez may not combine with Araray.

- [Q4h] The Ge'ez row must appear beneath Izzel and Araray (when present).

- [Q4i] The Izzel row must appear beneath Araray (when present).

- [Q4j] The tonal marks (non-letter symbols) apply only to the letter below.

- [Q4k] Annotations (abbreviated words, non-tonal marks) apply to the entire word below.

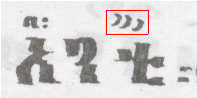

- [Q4l] Tonal marks may be stacked together within a row for emphasis.

- [Q4l] Annotations may not be stacked together.

- [Q4m] No more than 3 tonal marks may occur in a stack.